Idea behind optimisation-centric generalisations of Bayes

Idea behind optimisation-centric generalisations of Bayes

Summary Talk

I outlined my research mission in a recent talk linked here.

Scope

I am committed to advancing the foundations and methodology of optimisation-centric generalised Bayesian posteriors. My 3-year EPSRC fellowship will help me realise this vision by laying the necessary foundations. Over the course of this time, I will also establish my own research group on generalised Bayesian methods.

Background

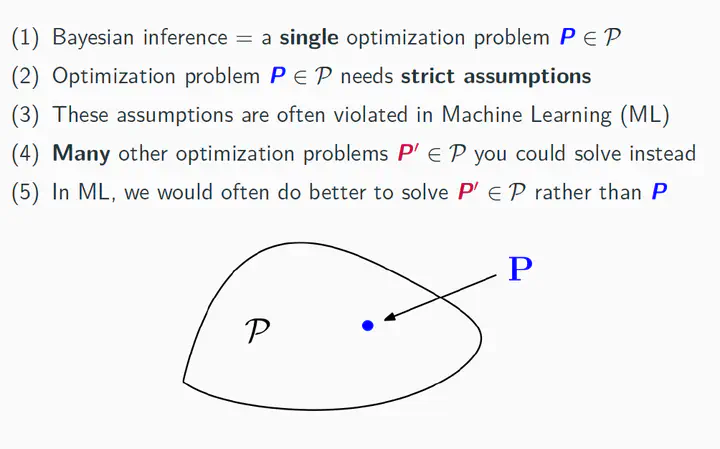

Arguably a fringe topic until even the early 1990s, Bayesian methods have become one of the most predominant statistical analysis frameworks in most of the sciences over the past two decades. Bayesian inference is attractive because data plays the role of updating one’s prior about the state of the world into a posterior belief. This has two advantages over other methods of statistical analysis: it allows for the incorporation of prior knowledge, and it provides a clear recipe for reconciling our prior beliefs with the true state of the world. While the standard Bayesian paradigm is conceptually elegant, operationalising it for statistical application requires at least three assumptions that are often unrealistic:

-

We need to pre-suppose that the true state of the world can be adequately described by an analytically available likelihood function indexed by some parameter—so that the degree of our prior knowledge about the real world is completely described by our prior knowledge about this parameter;

-

We have to assume that the statistical modeller is actually capable of explicitly formulating the full extent of her prior knowledge about this parameter in form of a probability distribution;

-

We need to surmise that the statistical modeller has enough computational budget so that the resulting Bayesian posterior belief can always be computed.

While these assumptions will never perfectly describe the reality of statistical analysis, they are a useful simplification within the classical paradigm of statistical analysis. In the classical paradigm, a domain expert with intimate knowledge of the natural phenomena that generated a data set D distills her expertise into a statistical model indexed by some parameter as well as a prior belief over reasonable values of said parameter. While this paradigm continues to adequately describe many scientific inquiries, the increasing availability of large scale data sets, computational power, and sophisticated black box models has given rise to a second way of performing statistical inference—the machine learning paradigm of statistical analysis. Where the classical paradigm was data-centric, the machine learning paradigm is model-centric: rather than seeking a parsimonious model that is hand-crafted to describe a single given data set D, models are instead intractable, overparameterised and often explicitly designed to adequately represent an inordinately large collection of possible data sets. In practice, this means that priors and models constructed in the machine learning paradigm are often determined before having knowledge about the nature of a data set to be analysed. Unfortunately, this violates assumptions 1 and 2 and leads to problems with misspecification. Beyond that, due to their aim of being near-universal black box modelling tools, statistical models specified in this way often are complex or intractable.

As a result, traditional Bayesian computation is infeasible, which leads to a violation of assumption 3. As a consequence, using standard Bayesian posteriors for inference within the machine learning paradigm is problematic for a number of practical reasons. These include a lack of robustness, ill-informed priors, and intractability. To address these problems, a number of generalised Bayes-like procedures have been proposed in the past: PAC-Bayes, Safe Bayes, and generalised belief updates. The optimisation-centric generalisation that I have introduced in my previous work recovers these pre-existing extensions, and axiomatically justifies a much larger class of generalised posterior distributions capable of addressing a variety of problems.

Use Cases

There is ample cause for further research on optimisation-centric generalised Bayesian methods: they reconcile the practices of modern large-scale inference with the assumptions underpinning Bayesian statistics. This has at least two significant practical advantages.

-

Enhancing Robustness: because it relies on assumptions 1 and 2, the standard Bayesian paradigm is not robust to poorly specified models or prior beliefs. Consequently, it results in misleading uncertainty quantification in various conditions that are frequently encountered in practice. This includes outliers, heterogeneous or contaminated data, and dependence of observations. Fortunately, generalised Bayesian posteriors overcome these issues and result in better uncertainty quantification.

-

Simplifying Computation: by virtue of its optimisation-centric nature, the generalisation studied as part of this fellowship can directly simplify computation relative to standard Bayesian posteriors. This has important ramifications for computationally intensive contexts such as intractable likelihoods, simulator-based inference, or variational methods in highly-parameterized models.

Some statistical applications that have already benefited from these developments are the following:

-

Time-ordered problems: due to their increased robustness, generalised posteriors have found great success in changepoint detection problems, sequential Monte Carlo methods, and more recently for regret guarantees in on-line learning.

-

Bayesian Machine Learning: black box models such as neural networks or Deep Gaussian Processes invariably suffer under model misspecification and poorly specified priors. Optimisationcentric generalised Bayesian posteriors can address both issues at once, and dramatically improve the reliability and robustness of uncertainty quantification in such models.